Crying at the Kitchen Table

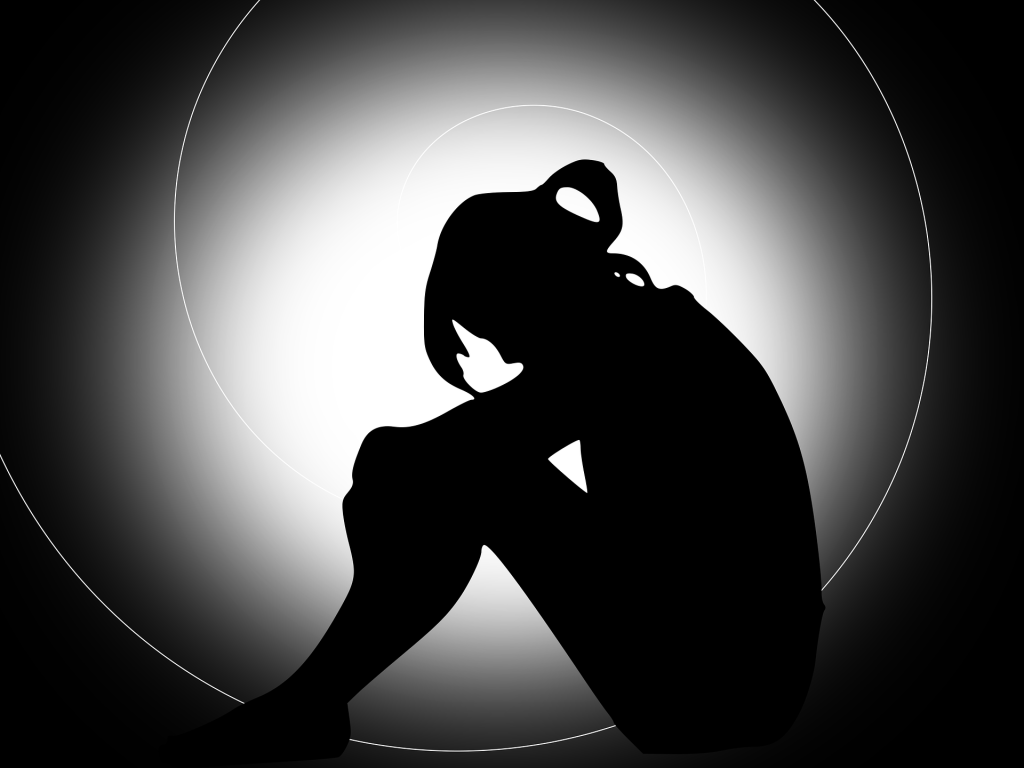

Jump in a time machine with me, and travel back to 1983. Allow me to set the scene. The setting seems standard enough as you see a woman and a child sitting together at a kitchen table. The child appears to be working on homework while the woman, presumably the child’s mother, oversees the attempt. As you look closer, you see that the child is red-faced and crying. While the woman attempts to guide the child along in the assignment, the child becomes more confused. No matter how patient and understanding the parent is, the poor child cannot grasp the concept. The child cries and begs to be free from the torture, but the two persist well into the night.

This scene was a common one in my household growing up. No matter how often the teacher explained concepts to me, something was missing between the teaching and the learning. I could not get it. I honestly cannot say that I remember much from early education other than many nights of the difficult interaction described above. I remember the struggle that learning presented for me. I remember believing I was “slow, stupid, and dumb” (please pardon the language, it was my reality at the time). Even when experiencing success, I found ways to fit those beliefs into my personal narrative. For example, once my third-grade teacher took me across the hall to show my second-grade teacher that I could finally read a complete sentence. Talk about mortifying being the last kid in school to learn to read. Around fourth grade, I underwent diagnostic testing. I cannot remember any specific supplemental instruction due to this diagnostic testing, but I do remember the label of being learning disabled. I do not know what my official diagnosis was or what learning disabilities they believed I had; nonetheless, I fully embraced this identity. I assumed that people were born with a set amount of intelligence and became convinced I did not get as much as others. As a result, I withdrew and became very shy. I mostly remember disliking my public school experience and having very low self-esteem due to my perceived inadequacies.

Despite having a negative personal account of public school, somehow, I survived. I went directly from high school to college because going to college was non-negotiable as far as my mother was concerned. I started at a community college with the basics (English, Math, and History), and it all came with many of the same frustrations. Nonetheless, when I took my first psychology course, I found a passion for learning about human development. I transferred to University for advanced studies, where I learned about behavioral theories extensively. I even still have some of my behavioral psychology textbooks. I remember learning about Ivan Pavlov’s experiments with classical conditioning with his salivating dogs and B. F. Skinner’s operant conditioning with pigeons. I reflected on ethical experiments on my computer-simulated program Sniffy the Virtual Rat, testing different reinforcement scales to see if I could increase or extinct a behavior. Overall, I found myself with a drive to understand the human experience. I sought to know how we make sense of the world in which we live. Fascinated by how an individual fits within society, my studies quickly expanded to include sociology and psychology. Once I tapped into passions and personal interests, there was a shift, and college became my own. So what changed? How did having an active interest in what I was learning about change my experience? How could I excel in advanced coursework for my majors if I was “learning disabled” and unable to learn (in my fixed mindset)? Something changed, and I think the key to my philosophy about learning lies within.

So what do/don’t I believe about learning?

As I evaluated my beliefs about learning, especially within the context of my advising role, I could not see my students as subjects like my time with Sniffy using reinforcements to drive behavior. I do not believe in an approach where advisors drag learners through learning goals (advisor-focused) via the use of reinforcement. Instead, learning is an active personal (learner-focused) process of continual engagement and reflection. As a result of my own experiences and the research performed while defining my learning philosophy, I believe that learning happens internally within the learner. I have experienced choice, ownership, and voice through authentic learning opportunities throughout the ADL Program (Harapnuik et al., 2018). Through efficacious uses of the program’s significant learning environments (Harapnuik, 2018), my learning experience grows and reshapes into rich and meaningful learning as my understanding evolves. Confirmed by research and personal experience, I believe that learners benefit from experience, guidance, and collaboration. We all bring our experiences and prejudgments to our learning experiences, and education requires a unique approach for each learner. I believe learning is an active process of continual engagement and reflection of the material, prior knowledge, related experience, and new understandings as concepts grow and connect with others. I believe that rich and compelling feedforward helps do this better than just working in a vacuum. Learning happens not just as a result of the material taught but through a learner’s interaction with the information, prior knowledge, and related experiences. Through this individualized learning, process concepts combine, grow, and link for greater understanding.

By taking a backward approach to defining what I believe about learning, I will first imagine what advising looks like to help pinpoint which learning theories support those goals.

How does learning happen?

My experience teaches me that we all hear and learn through our perceptions. An asynchronous environment and digital communication compound this phenomenon making it challenging to interpret tone and understanding. Therefore, I want to convey that my advisees are respected and valued, acknowledging our different histories and experiences with learning while believing that diversity makes our interactions rich and beneficial. Building an environment based on a philosophy supports the belief that an advisor’s role is facilitating communication and helping learners define meaning throughout their education (and beyond). At the same time, keeping my advisees in control by teaching them how and where to validate potential impacts on their futures. By building trusted relationships, I would like to assist them in reflecting upon their learning path and past. I want to help shift the focus to lessons learned, and opportunities gained instead of just the immediate goal of degree/certificate completion.

Which learning theory and theorists support my beliefs about learning?

Of the learning theories reviewed, Humanism and Constructivism are the two philosophies that support my belief that learning is individualized, internal, active, authentic, and autonomous. These two philosophies also support my desire to empower my learners through the foundation of relationship building required for reflection needed for continued growth—specifically through the work of Carl Rogers (Humanism) and Lev Vygotsky (Social Constructivism).

Learning is Individualized and Internal.

Both Humanism and Constructivism agree that learning is an internalized process that others cannot control. Learners bring various educational experiences, cultural backgrounds, and individual perspectives that impact learning. As such, How Pople Learn (1999) describes how personal experiences, the learners’ points of reference, and prejudgments can affect learning (Donovan et al., 1999, p. 19). These frames of reference allow learners to see and interact with the world through those filters. This understanding is so vital to the role advising plays. It is not uncommon to wrongly assume that students have similar skills and abilities when working with specific programs or that graduate students holding at least one degree already know how to be college students. Humanism and Constructivism acknowledge these views by recognizing that each person brings individual life experiences to the learning encounter. Constructivism expands on these notions by building on previous information in distinctive ways to create new information (Gandhi & Mukheriji, 2022; Harasim, 2017, p. 62; Pritchard, 2009, p. 17). Whereas Humanism believes all humans seek purpose and have an ingrained ambition to learn. Constructivism taps into those purposes and ambitions through curiosity and inquiry (Harasim, 2017, p. 71). Embracing the humanistic and constructivist perspectives, advising innovation must enter each advising relationship with non-judgemental acceptance of each learner’s experience before, during, and after their time with the institution (Bermea, 2022, p. 8). Recognizing that learning is individualized and subjective, I believe my learning philosophy must also be learner-centered. I do not view this learning philosophy as one would approach a teaching philosophy because the experience is about the learner, not the teacher (or, in this case, the advisor).

Learning is Active, Authentic, and Autonomous.

Deep and meaningful learning requires a philosophy that encourages active, student-centered, significant learning opportunities. “By thinking about advising as learning, one realizes the application of the principle that students learn through the active construction of knowledge” (Hemwall & Trachte, 2005, p. 77). Through this constructivist perspective, learners pursue information, experiences, and connections based on their goals and purpose. By returning this control to the learner, advising creates the opportunity for increased learner autonomy. Constructivism supports this through a “[focus] on the role of the learner” (Harasim, 2017, p. 70), and similarly, in Humanistic philosophies, the learners hold comprehensive oversight over their learning (Bermea, 2022, p. 7; Gandhi & Mukherji, 2022). Through complete ownership and authority, the learning that takes place is transformational. Through constructivist approaches, learners act as artists and architects of their understanding (Harasim, 2017, p. 70; Hemwall & Trachte, 2005, p. 77; Kitchener & Fischer, 1990). This shift in learning responsibility to the learner frees the advisor to act as a facilitator as the student works to process the meaning of their learning experience. Therefore, this learning philosophy must also address the advising relationship’s role in reflection.

Learning requires Relationship and Reflection.

The final but most important piece of the learning philosophy puzzle is to outline the advisors’ roles and, most importantly, their relationship with the learner. As advisors that care, we value being supportive encouragers. Believing that relationship building between advisor and student is a substantial contribution to each learner’s academic path and the institution’s purpose and goals, aligning with philosophies that contribute to creating these trusted relationships is paramount. As such, Humanistic philosophy is “based on a relationship rooted in trust and [emphasize] that the student [learns] from their past experiences” while “[emphasizing] the student’s free choice, values, and self-evaluation decisions” (Bermea, 2022, p. 5 & p. 7). Similarly, through constructivist philosophies, the advisor facilitates a level of contemplation and introspection about learning; the student assembles meaning and assigns value to their learning experience (Harasim, 2017, p. 62; Bates, 2015, pp. 59-60). Therefore, both Humanist and Constructivist philosophies align closely with my beliefs that advisors provide a beneficial function in each student’s academic journey.

Conclusion

As shown, advising presents an exciting opportunity to support learners as they balance life and create meaning throughout their academic pursuits. By establishing this learning philosophy which values the learners’ control within and beyond the learning environment, advisors can help students reflect, engage, and personalize their learning experience. With the guidance of both Humanistic and Constructivist learning theories, advisors can show kindness through compassionate guidance that allows the learner to grow and understand throughout their learning experience. Together, we can help ensure our learners never feel like that little girl crying at the kitchen table.

Annotated Bibliography

There were many sources reviewed in the process of evaluating my philosophy about learning. I had to review and catalog sources provided through the ADL Program and related modules. However, beyond those sources, I found that digging into related and creative sources helped me get in touch with my beliefs. There is so much more I want to research and learn about, but these references helped me frame my understanding of learning and create my learning philosophy.